Understanding More About Rudbeckia

The genus name “Rudbeckia’ honors Olof Rudbeck (1630-1702), a Swedish botanist and founder of the Uppsala Botanic Garden in Sweden where Carl Linnaeus was professor of botany.

Rudbeckia fulgida was first described by William Aiton in 1789 in Hortus Kewensis, a catalog of the plants cultivated in the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew. In 1945, Arthur Cronquist recognized four varieties of Rudbeckia including var. sullivantii, var. umbrosa, var. fulgida and var. missourriensis. Then in 1957, Robert Perdue, Jr., contributed a new scheme to Rhodora excluding var. missourriensis but adding four more varieties including vars. deamii, speciosa, palustris, and spathulata.

In 2013 the description of the Rudbeckia fulgida complex was revised again by Campbell and Seymour.

They define two subgroups of Rudbeckia:

Campbell and Seymour note: “The name Rudbeckia fulgida has been widely applied to most of the taxa treated in this paper, allowing much confusion in published ranges and habitats. Despite many reports, typical R. fulgida is unknown in mid-western regions, where most records probably refer to R. speciosa. Further south and east, there is also confusion due to apparent intergradation with R. tenax.

First subgroup

The fulgida-tenax subgroup (including R. speciosa and R. terranigrae) typically occur in grassy openings that are maintained by disturbance rather than just xeric or hydric extremes.

Rudbeckia fulgida var. fulgida may just represent a robust form of typical R. fulgida, but has been suggested as a distinct variant or transition to other taxa (such as R. tenax or R. umbrosa). Range: mostly in or near southern Appalachian regions, Piedmont and mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain; AL; GA, LA, SC, NC, VA, WV; D.C., MD, DE, NJ, PA. Habitat: open to slightly shaded areas, often disturbed such as along roads, but avoiding xeric or hydric extremes

Rudbeckia tenax Range: Interior Low Plateaus (mostly), southern Cumberland Plateau, southern Ridge & Valley, and locally on central Gulf Coastal Plain; IL, IN, OH, AL, GA, TN, KY, MI, FL. Habitat: xeric to xerohydric calcareous glades, thin woods and roadsides, often with red cedars; “dry woods and clearings”.

Notes from the authors. “This variable species was recognized by Small (1933) and Fernald (1950) but it has been largely overlooked for 50 years. Its stoloniferous habit and some detailed anatomical differences distinguish the species from true R. fulgida. Both taxa can become locally weedy on roadsides or similarly disturbed sites, and possible hybrids have been recorded from such sites where ranges overlap.”

Rudbeckia speciosa Range: mostly on Glacial Till Plains and extending along valleys into western Appalachian regions, including parts of the Allegheny Plateau and northern Ridge & Valley, perhaps also on the mid- Atlantic Coastal Plain; widely distributed but apparently local to rare as a native plant within most of its range: MO, IL, WI, northern KY, IN, MI, OH, PA, northeastern TN, southeastern NY, CT, MA, southern Ontario and southern Quebec. Habitat: generally base-rich soils (calcareous or dolomitic); “woods and bottomlands". It may be most common in thin woods and meadows on seeps or swales with a tendency to hydrological variation, while Rudbeckia tenax tends to be on more consistently xeric rocky sites, and R. sullivantii tends to be on more damp to marshy soils.

Notes from the authors: “Some largely sterile plants of this species have become widely propagated as ornamentals across eastern North America and Europe during the past two centuries. These plants were often named R. fulgida. … A cultivar … named “Viette’s Little Suzy” … (has been) distributed from nurseries in Ohio. The name “R. speciosa” has been widely misapplied to other taxa in the past. In particular, the name has been often allied with R. sullivantii in much recent literature.

Translation: The plant descriptions given by growers and Nursery Catalogs are confusing and often wrong when it comes to Rudbeckia! Maybe that’s one upside of plant patents - the breeder has to (sort of) tell what species were used in the process.

Just for the record:

Plant Patent Info for ‘Viette’s Little Suzy’ Patent number: PP8867 Granted 1994

Inventor: Mark A. Viette (Fishersville, VA)

Description: The present application comprises a new and distinct cultivar of Rudbeckia fulgida var. speciosa known by the cultivar name ‘Viette's Little Suzy’. The new cultivar ‘ Viette's Little Suzy’ is a mutation or sport of an unnamed and unpatented plant of R. fulgida var. speciosa, and was discovered and selected by the inventor Mark A. Viette in a cultivated area in Fishersville, VA. The new cultivar was growing in a bed of plants of its parent cultivar, and was immediately recognized due to its dwarf habit.

Characteristics of Viette's Little Suzy:

1. The overall height of Viette's Little Suzy averages only approximately 14 inches, as opposed to a typical height of approximately 28 inches or more for plants of the indicated species, including the parent cultivar from which the new cultivar mutated.

2. The leaves are shorter than the leaves of the parent cultivar and other known plants of the species, and the overall height of the foliage is only approximately 5-8 inches above ground level … The dwarf habit essentially maintains the proportion of foliage height to total plant height.

3. The ray florets of Viette's Little Suzy are bright yellow with the center of the flower being domed and comprised of disc florets dark purple in color. The overall flower diameter for a mature flower is approximately 2 inches, slightly less than mature flower diameters of the parent and other plants of its species. The cultivar is very floriferous.

4. The foliage color of the new cultivar is dark green for mature foliage, turning to a dark grayed-purple in the fall, apparently due to cooler temperatures. This color change is not expressed in the parent or other plants of this species.

Second subgroup

The umbrosa-palustris subgroup (including R. chapmannii, R. sullivantii, and R. deamii) occur typically on mesic to hydric sites, especially in calcareous seeps, fens, or similar habitats.

Rudbeckia sullivantii Range: Alleghenies, Mid-western Till Plains and Ozarks, plus scattered disjunctions mostly in or near the southern Interior Low Plateaus: MO, IL, IN, MI, OH. It is uncommon to rare across much of its range. Observations in the more eastern states like PA, NY, CT, MA are likely just from cultivation. Habitat: in or near fens, calcareous swales, seeps, riparian marshes, damp roadsides and ditches; “local in moist, wet or springy places about lakes and marshes and along streams and roadsides”.

Notes from the authors: “A form of Rudbeckia sullivantii was selected in Germany over 60 years ago to became the popular ornamental cultivar ‘Goldsturm’. It has relatively smooth robust shoots and profuse early inflorescences, but it often suffers from drought and leaf- spotting fungus (especially Septoria rudbeckiae). Recently patented selections from Goldsturm that have relatively short compact forms and long flowering seasons with less disease are “Early Bird Gold” and “Little Goldstar”; other named cultivars exist without patents. Analysis of Scott et al. (2007) revealed much overlap within Illinois in genetic markers between wild R. sullivantii and ‘Goldsturm’, but they found enough difference to recommend that ‘Goldsturm’ should not be used where gene flow into wild populations might occur.”

More about ‘Goldsturm’: Although native to North America Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’ was discovered in a Czechoslovakian nursery in 1937 by Heinrich Hagemann. The seeds of the wild form were originally shipped from the USA to The Botanical Garden of the University in Graz (Germany) and given to The Brother Schütz Nursery in Czechoslovakia (Gebrüder Schütz). The Nursery of Brother Schütz (located in Olomučany at Blansko) was well-established at that time and a recognized perennial nursery with central European connections, and was the nursery where Hagemann had started his career. Hagemann, who had become head gardener for world famous perennial breeder and grower Karl Foerster, was on a private visit to the Czech nursery, and he noticed and admired the compact habit and floods of blooms of this floriferous charmer, which had already been cultivated in the experimental flower beds.

Heinrich brought some plants back to Potsdam, Germany in 1937 and, along with Karl Foerster, began to grow and propagate them. Legend says that upon seeing the flowers for the first time in 1938, Karl Foerster called out 'Goldsturm!' (= 'Gold Storm').

Rudbeckia deamii Range: Till-plains of central IN, IL and OH; Interior Low Plateaus of southern IN . Habitat: mostly along streamsides and roadside ditches; “creek... bank... roadside ditch”; “wooded ridges and banks of streams”.

Notes from the authors: “This poorly documented species was initially discovered in 1914–17 along creek banks and roadside ditches of central Indiana by Amercian botanist Charles Deam (1865-1953). Rudbeckia deamii, as a variant of “fulgida,” has become widely grown in gardens since 2000. The plant is usually taller, more long-lasting in its flowers, and more drought tolerant than R. sullivantii. It is now much more common in cultivation than in the wild and often extolled by gardeners.”

Description of Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii by growers:

While there may be a bounty of black-eyed susan on the market, what makes Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii a dream is its ability to wrap strength, beauty, disease and pest resistance all into one neat package.

It is a clump perennial (doesn't spread by rhizomes) close to 3' tall and 2' wide, with very hairy leaves, and orange-yellow flowers. It is adaptable to virtually any soil - clay, loam, sandy, shallow. It prefers medium to moist soils, but can handle dry soils too. Best grown in sun, half shade. It flowers in late summer to early fall. It is a native wildflower to Illinois, Indiana and Ohio. Hardy in zones 3-9.

It is tolerant of drought, humidity & heat, deer and rabbit resistant - a relatively disease and pest free plant. For flower beds, naturalization, pollinator gardens, butterfly gardens, deer resistant landscaping, low maintenance landscaping,....An excellent durable perennial for ups and downs of future climate changes.

OK, so where did ‘American Gold Rush’ come from: (Hint, it’s NOT a cultivar of ‘Goldsturm’!)

From the Plant Patent:

BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION: The present invention relates to a new and distinct hybrid of Rudbeckia plant named ‘American Gold Rush’ characterized by the combination smaller hairy foliage and shorter height, compared to the seed parent. The new Rudbeckia was raised as a seedling from open pollinated seed sown from the seed parent Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii, not patented, in Hebron, IL. The selection of the new plant was due to its smaller hairy foliage and shorter height compared to the seed parent.

Characteristics

Parentage: Male or pollen parent an unknown Rudbeckia, female or seed parent Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii.

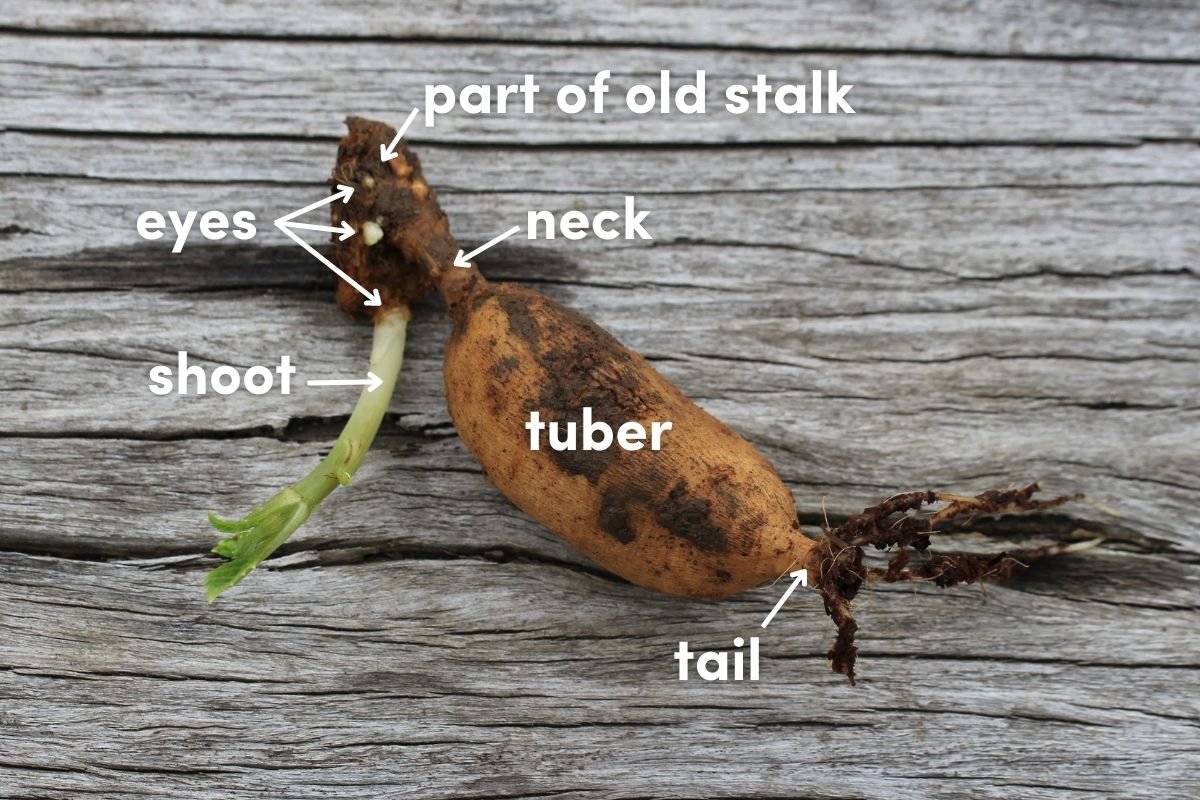

Root description: Fibrous, medium thickness, brown in color.

Root habit: Moderate branching, moderate density.

Plant description: Herbaceous perennial. Overall habit of the new Rudbeckia is a mound shaped clump, with branching stems topped by gold inflorescences starting in mid June.

Flowers:

• Single, composite on branched flowering stems.

• Position.—Borne on both terminal and axillary peduncles above the foliage.

• Number of inflorescences per plant.—Approximately 150.

• Arrangement.—Disc and ray florets.

• Bloom period and duration.—Mid June through mid-September. 4-6 weeks on the plant.

• Reproductive organs:

Androecium.—Quantity per disc floret, 5.

Pollen amount.—None observed.

Gynoecium present on ray and disc florets.—

Scent.—No scent noticed.

• Seed and fruit: None observed.

• Hardiness: Plants of the new Rudbeckia have been observed to be hardy to USDA Zone 5.

Plants of the new Rudbeckia can be compared to plants of Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii the seed parent, not patented.

1. The new Rudbeckia plant has a mature size measuring 36 cm high and 39 cm wide while Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii measures 120 cm high and over 60 cm wide.

2. The new Rudbeckia plant has a naturally mound shaped habit while Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii has an upright open habit.

3. The new Rudbeckia plant has smaller foliage approximately 25 cm long and 5 cm wide while Rudbeckia fulgida var. deamii has foliage that reaches approximately 35 cm long and 10 cm wide.

Notice: the patent says no pollen was observed and no seed or fruit was observed. I’m pretty sure that means the plant is sterile. That’s a good thing if you don’t want it to be able to cross-hybridize with the actual native plant in its range. But it also means that it has no genetic diversity that would allow it to respond to changing environmental conditions or stress situations.