More from the NYS Arborist Meeting in January:

Mr. Hendrickson, the guru from Bartlett Tree Research, mentioned a magic ingedient in passing that I didn't know anything about - biochar. It turns out that biochar has a rich history (no pun intended) as a soil amendment that "magically" makes plants and trees grow and that even helps soil structure and health.

Here are some facts:

Biochar is formed from organic material (otherwise know as garden waste) by pyrolysis: a thermochemical decomposition of organic material at high temperatures (390 - 570 degrees F) in the absence of oxygen. It involves the simultaneous change of chemical composition and physical phase, and is irreversible. The word is coined from the Greek-derived elements pyro "fire" and lysis "separating". In general, pyrolysis of organic substances produces gas and liquid products and leaves a solid residue richer in carbon content, char - aka biochar. Pyrolysis differs from other high-temperature processes like combustion and hydrolysis in that it doesn't involve reactions with oxygen or water.

Biochar as a soil amendment has an ancient precedent - "terra preta", discovered in the 1950s by Dutch soil scientist Wim Sombroek in the Amazon rainforest. It still covers 10 percent of the Amazon Basin. As the nonprofit U.S. Biochar Initiative explains, “biochar has been created and used by humans in traditional agricultural practices in the Amazon Basin of South America for more than 2,500 years. Dark, charcoal-rich soil (known as terra preta, or black earth) supported productive farms in areas that previously had poor and, in some places, toxic soils".

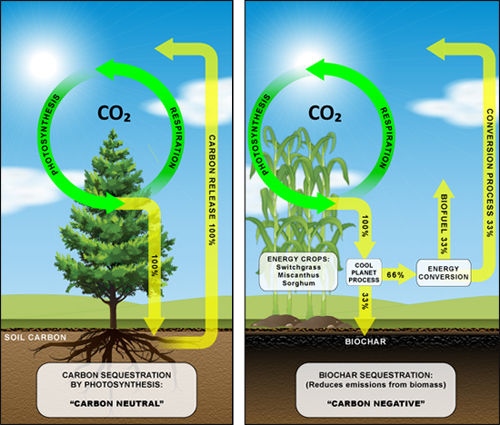

Over the past 10 years, researchers have been investigating terra preta, now called biochar, as an agricultural resource. Typically when biomass decomposes or burns, virtually all of the carbon stored in the plant is released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming. But when biochar is produced, roughly half of the plant’s carbon is retained as stable carbon in the biochar. The other half is released as wood gases, which can be used as an energy source. This biochar cycle puts carbon from the atmosphere back into the earth, puts it to positive use in the soil and increases the amount of time it stays there.

Here's why biochar is "magic":

- It provides a combination of moisture management and a way to store microbial food and plant fertilizer. When there is an excess of water, food and fertilizer, biochar stores them. When there is a deficiency, it slowly releases them back into the soil, where the plant or microbes can take advantage of them.

- It persists in the soil for years, greatly reducing(eliminating?) the need for re-application. It is much more persistent in soil than any other form of organic matter that's applied to soil. This is referred to as "stability" by the soil scientists.

- It is highly adsorbent. It sops up humic acid, a food for soil microorganisms, and humic acid itself binds to fertilizers, keeping them from leaching out of the soil.

"What is special about biochar is that it is much more effective in retaining most nutrients and keeping them available to plants than other organic matter such as for example leaf litter, compost or manures. Interestingly, this is also true for phosphorus which is not at all retained by 'normal' soil organic matter". (Lehmann, 2007)

from Cornell webpage; references as cited on that page

- It is also highly adsorbent of water. In conditions with greater than 60% relative humidity, it absorbs water. And in conditions less than 40% relative humidity, it releases water. So it is an enormous stabilizer of relative humidity in soil, which means less watering.

- It is a way to "recycle" organic waste, and the off-gas can be used as fuel.

- You only need a little, and it can be added as a soil amendment to existing planting beds, like tree wells.

But there are caveats as well:

- The vast majority of research has been into biochar's effects on agricultural soils and crop yields. Until very recently, there has been little research on biochar in urban and suburban soils, trees and shrubs. Agricultural crop research goes a lot faster than urban tree growth research - that will take years.

- All biochar is not created equal - it matters what organic matter was used to make it and whether it has been tested for contaminants and properly de-watered.

- This is not a plug - but Bartlett uses biochar as part of their soil improvement and root invigoration treatments. Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories is collaborating with the Morton Arboretum to look at the effects of adding biochar to existing tree wells in Chicago.

- Mr. Hendrickson said that Bartlett has a supplier that they have vetted extensively.

Here are some of the initial findings that Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories and the Morton Arboretum have publicized for biochar:

- Biochar can have a measurable positive impact on both soil quality and plant growth.

- Biochar works best in combination with compost. Biochar itself doesn't provide nutrients, but compost does. So when you mix them together, you're "charging up" the biochar with nutrients. Their research also suggests that biochar improves the performance of compost - i.e. when the two are blended, trees and shrubs show better growth than with either of the two alone.

- More is not necessarily better - in fact it can be deleterious. (like anything!) Their research is trying to determine the optimal amount, but they already know that a little bit goes a long way.

- Biochar may also promote disease resistance - this is only preliminary greenhouse-based research but will be looked at in future studies.

To find out more:

soils.org is an interesting website - this link will lead you to a story about the Morton Arboretum work on tree growth using biochar

And, of course,Cornell has a lot of expertise - this link will provide you with both information and lots of references